You want to know which spread fits your life: butter made from cream or margarine made from vegetable oils. Butter is a natural dairy product with more saturated fat, while margarine is made from plant oils and usually has more unsaturated fat, so your choice affects taste, cooking behavior, and heart-health trade-offs. I’ll guide you through the key differences so you can pick what works for your meals and health.

I write this with Emma Reed’s work in mind and pull from nutrition and food science to keep things practical. Together we’ll look at how each is made, how they behave in the kitchen, and what to watch for on nutrition labels so you can decide with confidence.

Key Takeaways

- One comes from cream and one from processed oils, and that changes fat type and flavor.

- Nutritional impact hinges on saturated versus unsaturated fats and added ingredients.

- Choose based on cooking needs, health goals, and label checks.

Contents

Defining Butter and Margarine

I will explain what each product is, how they’re made, and the main ingredients that shape their taste, texture, and uses.

What Is Butter?

I make butter by churning cream from cow’s milk until the fat separates from the buttermilk.

This process yields a product that is mostly milk fat with small amounts of water and milk solids. Butter’s flavor comes from the cream and sometimes added salt. Dairy butter melts at a moderate temperature, which makes it useful for baking, sautéing, and spreading.

Butter naturally contains saturated fats, fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K), and trace lactose or milk proteins. Clarified butter, or ghee, has water and milk solids removed and tolerates higher cooking temperatures. I note that butter’s animal origin matters for people with dairy allergies or those choosing plant-based diets.

What Is Margarine?

I describe margarine as a manufactured spread designed to mimic butter’s texture and flavor.

Producers typically start with vegetable oils, then process them so the oils are solid or semi-solid at room temperature. This processing can include hydrogenation, interesterification, or blending, and it influences melting behavior and shelf life.

Margarine formulations vary widely: some aim for low saturated fat, others for better spreadability straight from the fridge. Manufacturers often add emulsifiers, colorings, and flavorings to achieve a butter-like profile. I mention that some margarine contains trans fat from older hydrogenation methods, though many modern brands use safer processes to avoid trans fats.

Basic Ingredients

I list the core ingredients for quick comparison:

- Butter: cream (milk fat), sometimes salt.

- Margarine: vegetable oils, water, emulsifiers, salt, and flavor/color additives.

Butter’s composition is simple and mainly dairy fat. Margarine blends multiple plant oils (soy, canola, sunflower, palm) to reach a specific fat texture.

Emulsifiers like lecithin keep water and fat mixed in margarine. Stabilizers and preservatives extend shelf life. Some margarines add vitamins A and D to match butter’s nutrient profile.

I also point out labeling cues to check:

- Look for “contains milk” on butter and possible “partially hydrogenated” on older margarine labels.

- Check the fat sources if you avoid palm oil or have allergies.

Production Processes

I explain how each spread starts and what changes it during making. You’ll see the role of milk and cream for butter, and oils and processing steps for margarine.

How Butter Is Made

I begin with fresh cream, usually from cow’s milk.

I cool the cream and churn it, which agitates fat globules until they clump and separate from the liquid (buttermilk).

After churning, I drain the buttermilk and wash the curd to remove remaining milk solids and lactose.

I then knead or work the butter to get a smooth texture and to even out moisture. Salt may be added at this stage for flavor and preservation.

Finally, I package butter in blocks or tubs, keeping it refrigerated to slow spoilage.

Key specifics:

- It takes roughly 20 liters of milk to make about 1 kg of butter.

- Temperature control during churning and working affects texture and spreadability.

How Margarine Is Produced

I start with vegetable oils such as soybean, sunflower, or canola oil.

I refine and sometimes partially hydrogenate or interesterify these oils to make them solid at room temperature.

Next I blend the fats with water, milk solids (optional), emulsifiers, salt, and flavorings to mimic butter.

I use high-shear mixers and an emulsification step to create a stable spreadable emulsion.

I then cool and crystallize the fat blend in a controlled way to set the final texture before packaging.

Key specifics:

- Manufacturers often add emulsifiers (like lecithin), artificial butter flavor, and colorants.

- Process steps are designed to meet legal fat content standards (often ~80% fat).

Differences in Manufacturing Methods

The core difference is raw material: dairy fat versus plant oils.

Butter relies on a biological separation (churning cream) with minimal processing. Margarine uses chemical and mechanical processing to turn liquid oils into a solid fat network.

I control texture in butter mainly by mechanical working and temperature.

In margarine, I adjust fat composition, hydrogenation/interesterification, and cooling schedules to achieve similar spreadability.

Preservation also differs: butter’s shorter shelf life needs refrigeration, while margarine often contains stabilizers and antioxidants for longer shelf stability.

Quick comparison table:

- Raw material: butter — cream; margarine — vegetable oils

- Key process: butter — churning; margarine — hydrogenation/interesterification + emulsification

- Additives: butter — usually salt; margarine — emulsifiers, flavors, colorants

Nutritional Comparison

I compare fat types, vitamins, minerals, and calories to help you choose between butter and margarine. The differences come down to saturated vs. unsaturated fats, added nutrients, and nearly identical calorie counts.

Fat Content and Types

Butter is mostly dairy fat and contains about 51–55% saturated fat of its total calories. That higher saturated fat raises LDL cholesterol more than most unsaturated fats. Margarine is made from vegetable oils and usually has more polyunsaturated and monounsaturated fats, which tend to lower LDL when they replace saturated fat.

Watch for trans fats in older stick margarines; they raise LDL and lower HDL. Many modern margarines now list “0 g trans fat” or use blends of oils and interesterification to avoid trans fats. For heart health advice and current guidance on fats, I refer to resources like the American Heart Association.

Vitamins and Minerals

Butter naturally contains small amounts of fat‑soluble vitamins, especially vitamin A and trace vitamin D if from fortified milk. It also supplies short-chain fatty acids and some cholesterol, which carry fat‑soluble nutrients in the body.

Margarine is often fortified with vitamins A and D to match or exceed butter’s levels. Some brands add plant sterols or omega‑3s too. I check labels: fortified margarines can be a useful source of vitamins for people who avoid dairy. For reliable nutrient data and fortification standards, I use tables from the USDA FoodData Central.

Caloric Values

A tablespoon of butter and a tablespoon of margarine contain similar calories—usually around 100 to 110 kcal. The small calorie difference comes from water content and formulation, not from one being “much lower” in energy.

Portion control matters. Using less of either spread cuts calories the same way. I read nutrition labels to compare serving sizes, since different brands list slightly different gram weights per tablespoon.

Health Considerations

I focus on the fats and risks that matter most when choosing between these spreads: how each affects cholesterol and heart disease, and whether margarine contains harmful trans fats.

Impact on Heart Health

I look at the types of fat in each spread because they change cholesterol differently. Butter has mostly saturated fat and raises LDL (“bad”) cholesterol more than unsaturated fats do. Higher LDL links to greater risk of heart disease over time.

Margarine is usually made from plant oils and contains more unsaturated fat, which can lower LDL when it replaces saturated fat in the diet. That can reduce cardiovascular risk for many people. I pay attention to labels: margarines high in unsaturated fat and low in trans fat are generally better for heart health than butter, especially for people with high cholesterol or a heart condition.

Trans Fats in Margarine

I watch for trans fats because they raise LDL and lower HDL (“good”) cholesterol, increasing heart disease risk. Older margarines used partially hydrogenated oils that created trans fats. Those were clearly linked to worse heart outcomes.

Today many brands use non-hydrogenated oils or interesterified fats to avoid trans fats. I check the Nutrition Facts and ingredient list for “partially hydrogenated” or any trans fat per serving. Even small amounts matter over time, so I favor products labeled 0 g trans fat and list no partially hydrogenated oils.

Taste and Culinary Uses

I describe how butter and margarine taste and how I use each in cooking so you can pick what fits your recipes and budget.

Flavor Profiles

Butter has a rich, creamy flavor from dairy fat and small milk solids that give it a slightly sweet, caramel-like note when browned. I notice real butter boosts savory dishes, sauces, and plain toast with a depth that margarine rarely matches. Salted butter adds another layer; the salt brightens flavors in finished dishes.

Margarine tastes milder and more neutral because it’s made from vegetable oils and added flavorings. I find it works well when you need fat without a strong dairy note, like in some spreads or savory bakes. For detailed food safety and fat composition differences, see the USDA guidance on fats and oils.

Baking and Cooking Applications

In baking, butter gives better flavor and flakier textures for pastries, pie crusts, and cookies because of its water content and milk solids. I use butter when I want browning and a tender crumb. Margarine can work in cakes or quick breads, especially stick margarines formulated for baking, but results may be softer or less crisp.

For cooking, I brown butter for sauces and pan-fry to add nutty aroma. Margarine holds up in high-volume, budget-sensitive cooking and in vegan or dairy-free recipes when labeled accordingly. When substituting, I match fat content and account for added water in butter; swapping 1:1 works for many recipes, but I tweak baking moisture and baking times as needed.

External resources: USDA fats and oils information and a pastry guide at King Arthur Baking help with technical details.

Dietary and Lifestyle Factors

I look at how butter and margarine fit into common eating patterns and health goals, and I note key allergy and intolerance issues that affect choice.

Suitability for Different Diets

I recommend butter for low-carb or keto diets because it is mostly saturated fat and adds calories without carbs. People watching cholesterol or heart disease risk often choose modern, trans fat–free margarines made from vegetable oils. Those margarines usually have more polyunsaturated and monounsaturated fats, which can help lower LDL cholesterol when used instead of butter.

For plant-based or vegan diets, I prefer plant-based margarines clearly labeled “vegan.” They avoid dairy and lactose. If you follow a whole-food or minimally processed plan, I suggest choosing high-quality butter from pasture-raised dairy or minimally processed spreads labeled simple-ingredient; otherwise, pick margarines with no trans fats and short ingredient lists.

Allergies and Intolerances

I check labels first for people with milk allergies or severe lactose intolerance. Butter contains dairy proteins and small lactose amounts, so it can trigger reactions in those with milk allergy. Clarified butter (ghee) has less lactose and protein, but it still risks reactions in very sensitive people.

Margarine can contain soy, nuts, or emulsifiers that cause allergies. I advise reading ingredient lists for “soy lecithin,” “tree nuts,” or “wheat” if you have specific allergies. For lactose intolerance, most margarines are safe since they are made from vegetable oils, but cross-contamination or added dairy can occur, so I look for “dairy-free” or “vegan” labels.

Economic and Environmental Aspects

I compare cost, market factors, and the environmental effects of butter and margarine. I focus on price drivers, production inputs, and the main sources of greenhouse gas and land use impacts.

Pricing Differences

I find butter usually costs more per pound than margarine in most markets. Butter’s price reflects dairy herd costs, milk collection, seasonal milk supply, and processing into cream and butterfat.

Margarine tends to be cheaper because manufacturers use lower-cost vegetable oils (soy, palm, sunflower) and industrial processing. Brand positioning matters: premium European-style butters and organic/biodynamic butter sell at higher prices, while store-brand margarines compete on low price.

I note price volatility differs. Butter prices can spike with changes in milk supply or feed costs. Margarine prices track vegetable oil markets, which respond to crop yields, trade policy, and palm oil demand. For budget shopping, margarine usually stretches dollars further.

Sustainability and Environmental Impact

I assess greenhouse gas emissions, land use, and water needs for both products. Butter’s largest impacts come from dairy farming: methane from cows, feed production, and manure management. Those factors raise GHG emissions per kilogram compared with most plant-based spreads.

Margarine’s key impacts depend on the oil used. Sunflower or canola oil generally has lower emissions than dairy. Palm oil can deliver low per-ton yields but often drives deforestation and biodiversity loss if not certified. I pay attention to sourcing: certified sustainable palm (RSPO), non-GMO and organic oil supply chains reduce specific harms.

I recommend consumers weigh labels and sourcing. Choosing butter from low-impact dairies or selecting margarine made from responsibly grown oils can change the environmental outcome significantly.

Regulations and Labeling

I follow U.S. rules that require clear labeling for margarine and similar products. The law says packages must show the word “margarine” or “oleomargarine” in type at least as large as any other name on the label. This helps consumers spot the product type at a glance.

I check ingredient lists and standards of identity when comparing butter and margarine. Butter is regulated as a dairy product with set fat and milk solids levels. Margarine must meet its own standards and cannot be labeled to mimic butter if it fails those rules.

I watch for nutrition and claims on the front of packages. Labels often show trans fat, saturated fat, and whether oils are partially hydrogenated. Honest labeling matters because it affects health choices.

I use this quick reference to read labels:

| What to look for | Why it matters |

|---|---|

| Product name (butter vs. margarine) | Indicates legal category |

| Ingredient list | Shows dairy vs. vegetable oils |

| Fat and trans fat per serving | Impacts health risks |

| “Spread” or modified name | May mean lower fat or added water |

I also note that other regions, like the EU, have their own rules on butter and spreads. Always read local labels when buying outside the U.S.

Historical Context and Consumer Preferences

I explain how butter and margarine began, changed over time, and why people choose one over the other today. I focus on origins, health debates, and shifting buyer habits.

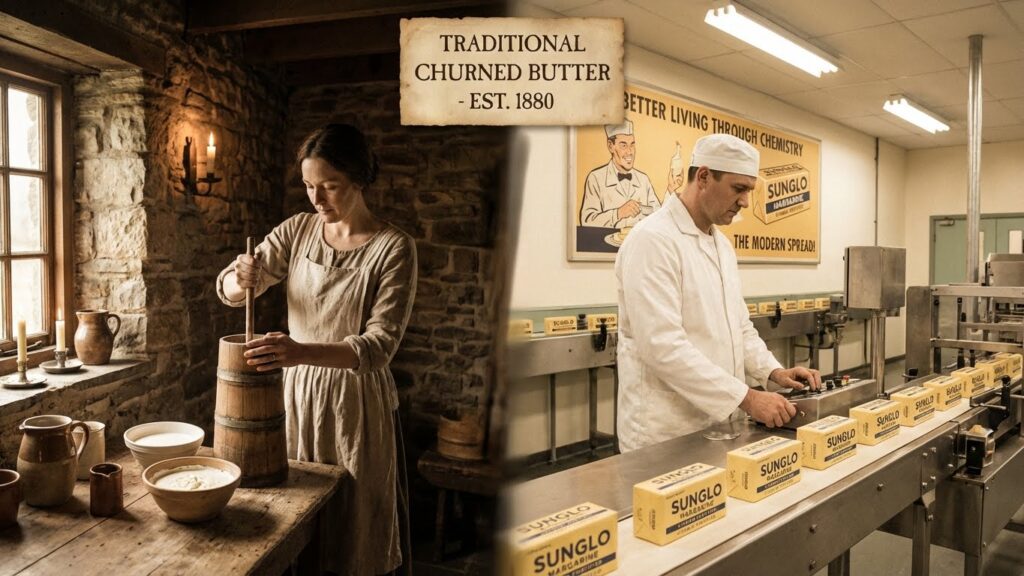

Origins and Evolution

I trace butter back to simple dairy farming and hand-churning of cream into a high-fat dairy spread. Producers made butter for home use and local markets; it stayed common where cows and cream were plentiful.

Margarine started in the 19th century as a cheaper alternative. Chemists created it from animal fats and then from vegetable oils. Governments and dairy groups often fought margarine’s market entry with taxes and labeling rules.

Industrial processing shaped margarine’s texture and shelf life. Early versions contained trans fats from partial hydrogenation, which later raised health concerns and led makers to change recipes.

Today, margarine recipes use interesterification or full hydrogenation and more unsaturated vegetable oils. I note that product formulation, not just origin, defines how each spread performs in cooking and nutrition.

Trends in Popularity

I point out that butter regained popularity in recent decades as consumers favored natural and minimally processed foods. Taste and culinary performance—flavor, browning, and texture—helped butter’s comeback.

Health research also shifted consumer views. When older margarines contained trans fats, demand fell. After reformulation reduced trans fats, some shoppers returned to margarine for lower saturated fat content.

Market trends now reflect diet and sustainability concerns. Plant-based diets boost interest in margarine and plant spreads, while organic and grass-fed labels help butter appeal to certain shoppers.

I list the main factors shaping choice:

- Flavor and cooking behavior (butter favored)

- Health profile and fat type (mixed results)

- Cost and availability (margarine often cheaper)

- Environmental and ethical concerns (influences vary)

FAQs

How do they differ in taste and cooking?

I find butter gives richer flavor and browns better for baking. Margarine can work for spreads and some recipes, but baking results may vary by brand.

Are there safer margarine choices?

Yes. I look for margarines labeled zero trans fat and those made with liquid vegetable oils instead of partially hydrogenated oils. Plant-based spreads with olive or canola oil are better options.

Which is better for heart health?

I recommend limiting saturated fat from butter and avoiding trans fats in margarine. Choosing soft margarines made from unsaturated oils usually supports heart health more than clarified butter heavy in saturated fat.

Can people with lactose intolerance use margarine?

Often yes, since many margarines contain little or no dairy. I always read the ingredient list because some contain milk solids.

How should I store them?

I keep butter in the fridge for freshness and use a butter dish for short-term softening. Margarine usually stores well in the fridge and follows package guidance.

Conclusion

I weighed the main differences between butter and margarine: origin, fat type, and how they behave in cooking. Butter comes from cream and has more saturated fat and cholesterol. Margarine is made from vegetable oils and usually has more unsaturated fat.

I recommend choosing based on taste and health needs. If you want rich flavor and bake better structure, butter often works best. If you need lower saturated fat or want a plant-based option, choose margarine or a plant-based spread.

I suggest checking labels for trans fats and hydrogenated oils. Pick products with minimal processing and clear ingredient lists. For heart health, I prefer spreads higher in unsaturated fats.

I keep portion sizes small no matter which I use. Both are calorie-dense, so a little goes a long way. I focus on overall eating patterns rather than one ingredient.

Bold choices help pick the right product:

- Choose butter for flavor and traditional baking.

- Choose margarine for lower saturated fat or vegan needs.

- Read labels to avoid trans fats and excess additives.

I find this practical approach helps readers make simple, informed choices that fit their tastes and health goals.